Friends of the l1ght!

L1GHTB1TES has moved. Its new permanent home is at l1ghtb1tes.com. This wordpress site will be discontinued in the coming weeks and will serve only as an archive. Please read this article HERE and visit l1ghtb1tes.com to subscribe and receive regular updates.

Thank you! See you there!

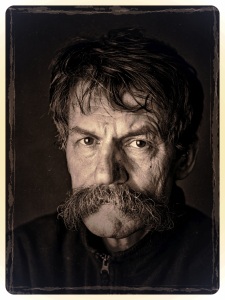

GL: I was lucky enough to be in your studio when you took this picture. I have never seen anyone actually use such an ancient, large format camera and I had the impression that you were ‘just’ taking a picture. It was about an hour later, when you developed and showed me the 8”x10” negative that I realized that looking at it was drawing me into a mysterious world, where everything was in some ways more real than the person who has just left the studio.

JPW: I took this picture as part of an ongoing photographic project which I’m calling “Local”. This is a series of large format portraits using black & white sheet film and a full plate field camera.

Being something of a photo historian, I am interested in old things. Old cameras, old film, old, often dead photographers. I am also intrigued when technologies can be stripped down to their most basic forms. A paper plane floating through the air is fascinating and delightful. A 747 jet, although the same principle may be involved, is alien and somewhat intimidating. I feel the same about cameras. The camera which I am using for this project, is a more than 100 year-old Sands and Hunter full plate bellows camera, made on the Strand, in a location which now sells a superior make of umbrellas, if I’m not mistaken.

GL: This picture is the opposite of what you’re doing as a wedding or a street photographer, when you’re catching amazing moments. Here you prepare for you picture. But in the end, you’re still capturing a single moment that needs to reflect something essential about your subject. How would you describe the difference between street or documentary photography and studio photography in this creative/emotional sense?

JPW: This is a complex question as it points to both the underlying common project of photography as well as its diversity. The most obvious answer – although not necessarily the most accurate or complete one – might be that most street photography is more or less captured through stealth. Hence the enduring appeal of the small, quiet Leica and Contax cameras. Small and quiet but also so fast and intuitive that one can capture shots which no other system could achieve. An old and enduring argument is that through stealth, one captures a more intimate, private, unguarded representation of the subject since they are unaware of the act of photography.

On the other hand, when there is a more explicit “contract” between photographer and subject – when the subject is aware of having their photograph taken – then this may elicit a whole gamut of responses as the subject attempts, perhaps even struggles, to project the desired construct which, somewhere in their psyche, they perceive as being most representative of who or what they are.

This rarely happens in fast street photography. Subjects generally don’t have the time to gather their wits enough to give this idea of self representation / projection a great deal of thought. But it does happen when the contract between photograph and subject is more explicit. And it is here that portrait photography becomes, for me, more intriguing. With stealth photography, a photographer can choose their moment and record, or even, to a certain degree, construct narrative within an image, shooting in such a way as to elicit or provoke a certain conjecture about the subject’s place in and relevance to the environment in which they have been observed and subsequently frozen.

This can be interesting enough, but it is the nature of street photography, or street portraiture even, that the identity of the subject is very much woven into the wider environment and narrative of the “street”.

GL: I’ve seen you work in your studio. You moved with a clear purpose. There was nothing stealthy about your approach. The opposite: I felt like you were going for ‘the kill’ with an undeniable determination.

JPW: A studio is more like a laboratory; empty, functional, faceless, it generally has no other purpose than to examine the subject under totally controlled conditions. The lighting is controlled by the photographer. The subject, to a degree, is controlled by the photographer, in terms of clothing, physical position, even facial expression in the more commercial examples. But the major difference between studio and most street photography/portraiture is the nature of the contract. For a start, it is undeniably there. The minute a subject steps into a studio there is a set of shared, although often elusive, even contradictory expectations. And it is how this contract plays itself out in the image which often makes the “straight-up” portrait such a fascinating document. A straight up portrait often says as much about responses to photography itself as it does about the subject. In fact, one could go so far as to say that this is what straight up portraiture actually is; a document recording a subjects response to the action of being photographed.

JPW: A studio is more like a laboratory; empty, functional, faceless, it generally has no other purpose than to examine the subject under totally controlled conditions. The lighting is controlled by the photographer. The subject, to a degree, is controlled by the photographer, in terms of clothing, physical position, even facial expression in the more commercial examples. But the major difference between studio and most street photography/portraiture is the nature of the contract. For a start, it is undeniably there. The minute a subject steps into a studio there is a set of shared, although often elusive, even contradictory expectations. And it is how this contract plays itself out in the image which often makes the “straight-up” portrait such a fascinating document. A straight up portrait often says as much about responses to photography itself as it does about the subject. In fact, one could go so far as to say that this is what straight up portraiture actually is; a document recording a subjects response to the action of being photographed.

GL: What do you see in the tramp’s eyes?

JPW: The image of the tramp is a particularly powerful, albeit elusive example of all this. I could have shot him any number of times, walking to and fro around the local backstreets, and this may have yielded interesting results. But the studio image really struck me. It is a young man, shabby, with a poor posture, peering into the camera with large brown eyes. But the eyes give nothing away. He meets what he must understand will be the public’s gaze with a sort of weary pragmatism, disinterest, even. It is a gaze which reveals absolutely nothing at all. It is entirely unengaging – and hypnotic.

The clothes, the posture, the mad, frazzled hair are all indicators of what should be an individual under a certain degree of stress. And yet he appears as calm as Buddha.

The image of the local tramp, for me at least, is one of the better examples in this series of portraits, of what we might call, (trivially perhaps), the “enigmatic” in straight up studio portraiture.

GL: You’re obviously emotionally attached to your equipment. What is your full plate camera like?

JPW: It is remarkably easy to use, particularly when used in a studio environment. I rebuilt the original lens board to take a more modern Compur, 8″ lens, yielding a moderately wide angle of view for an 8”x10” format. The camera is a full plate 10”x12″ format, but I masked off the viewing screen so that I can shoot 8×10″ film in the modified dark slides.

I chose this format through historical interest, but also because large format, as distinct from 35mm, is a very, very different experience altogether, both for the photographer and certainly for the subject. Peering into a 100-year-old antique machine, for probably the first (and last) time in one’s life, can elicit an entirely different response than a grab shot on a smaller, hand-held format.

I chose this format through historical interest, but also because large format, as distinct from 35mm, is a very, very different experience altogether, both for the photographer and certainly for the subject. Peering into a 100-year-old antique machine, for probably the first (and last) time in one’s life, can elicit an entirely different response than a grab shot on a smaller, hand-held format.

GL: So is large format a technical or a philosophical choice for you?

JWP: Well, the results are breathtaking. There is a level of detail which 35mm, or even medium format could never hope to achieve. And it is this which, at the technical, or optical level if you like, lends these images such an immediate, inescapable veracity. A tangeable, almost shocking realism which, as the format gets larger and larger, reveals more and more, in my opinion, of the central tenets of what photography actually is: the power it can wield as a document of not only reality but also, in a sense, meta, even super-reality.

It talks and elicits responses about reality which is not something we naturally do. Our perceptions of reality are at best, dubious, at worst, chaotic, barely considered at all. Looking at a photograph is like stopping time and space – which is precisely, at the technical level, what a photograph is. My point is that when an image also yields a level of detail to be studied, at our leisure, in a way we could never, ever hope to achieve in our everyday scrutiny of the world, then the image, as I say, becomes not only a document of reality, but a document about reality. There is only one other artistic, intellectual enterprise that I can think of which comes close to achieving this – I mean provoking and challenging thought and conjecture about what we think we mean when we consider reality – and that is not a great departure from meta-realism, in a word, surrealism.

GL: How do you light these portraits?

JPW: It was and is important to me that all these images are lit and shot in exactly the same way. I may shoot tighter or looser depending on the relevance of body shape, clothing, posture etc, but the light is the same, one large soft box over a Bowens strobe, a large reflector set to the other side, a reasonable amount of distance between the subject and the background to yield a little blur, and that’s it.

JPW: It was and is important to me that all these images are lit and shot in exactly the same way. I may shoot tighter or looser depending on the relevance of body shape, clothing, posture etc, but the light is the same, one large soft box over a Bowens strobe, a large reflector set to the other side, a reasonable amount of distance between the subject and the background to yield a little blur, and that’s it.

The reason for keeping everything the same, however, is that it is important to me that the photography doesn’t get in the way, so to speak. It all needs to be democratic and even-handed, otherwise there would naturally be issues as to why I shot one subject in a certain way and not another. It is important, if the subjects are to be given any kind of voice, however elusive that voice may be, that the hand of the photographer is as unobtrusive as possible.

GL: What about aperture and shutter speed? What motivates your choices?

JPW: I used a light meter on the first couple of shots and got f/22 – f/32. I still check but it’s pretty much a formality now. Shutter speed doesnt mean a great deal but I keep it at around 1/125th as older lenses can start to get a bit suspect at slower speeds. The aperture is more important of course, particularly shooting on such a huge format. The larger the format, the shallower the depth of field when shooting at equivalent distances since the focal lengths become longer and longer.

In short, shooting at f/5.6 is virtually impossible, and largely pointless. Besides, I don’t want massively shallow depth-of-field, I’m going to get them anyway on the tighter shots, even at f/22!

GL: Do you work with your portraits in post?

JPW: With regards to post-production, I’m very sorry to admit that I scan the images. I want to, and will, contact the negatives onto double weight fibre based paper at some point, but right now, the quickest way of getting the images out there is, of course, to scan. It’s a pity, as the whole thing just winds up as pixels again, but it doesn’t make a great deal of difference to the online viewing experience. Well, it makes no difference at all beyond the purely intellectual objection of knowing they are scans and not prints….because I just told you!

JPW: With regards to post-production, I’m very sorry to admit that I scan the images. I want to, and will, contact the negatives onto double weight fibre based paper at some point, but right now, the quickest way of getting the images out there is, of course, to scan. It’s a pity, as the whole thing just winds up as pixels again, but it doesn’t make a great deal of difference to the online viewing experience. Well, it makes no difference at all beyond the purely intellectual objection of knowing they are scans and not prints….because I just told you!

(To see more of Jason Pierce-Williams’ pictures visit his website at wwww.jasonwilliamsphotography.com. All images © Jason Pierce-Williams and are reproduced with the permission of the author.)

György is a cinematographer teaching photography courses in London. To book a class or for more information visit www.dslrphotographycourses.com.